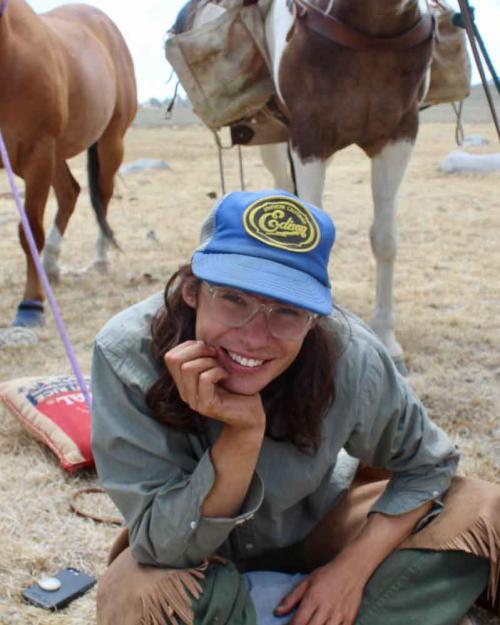

Like many students who had an amazing summer, Milo Vella ’23 is starting the semester thinking about how he will incorporate that experience into his senior thesis.

Vella, a Robert S. Harrison College Scholar in the College of Arts & Sciences, spent his summer gardening for the Big Pine Paiute Tribal Environmental Department and the Indian Water Commission in Owens Valley, Calif. His experience this summer built on a spring break trip from last year, funded by the student-run Community Partnership Funding Board, advised by the David M. Einhorn Center for Community Engagement.

Vella is interested in “food sovereignty” within Indigenous communities – a growing field of work and study focused on the connections between food, food systems, place, nutrition and Native peoples’ right to plan for their own future.

“Against all odds, Nüümü , the Paiute people of the Owens Valley in California, have endeavored to maintain their place-specific food systems since the intrusion of European settlers onto their territories,” Vella said. “Many of these communities and their governments are working to re-establish certain elements of their rich heritage foodways which hold continuing relevance in the face of contemporary crises.”

The movement involves not only re-establishing heritage foods, but also bolstering the systems that sustain them: irrigation and land access, for instance.

Vella’s spring work included organizing a series of workdays and free lunches at the Big Pine Tribal Community’s demonstration garden, featuring food purchased from Indigenous agricultural enterprises from across the U.S. Those products included roasted flour from the Iroquois White Corn Project, heritage tepary beans from the Gila River Reservation, and wild rice and foraged berry preserves from the Red Lake Nation.

“It was an exciting way to support food sovereignty programs across a large swath of territory and share the food with others, with reciprocity and gratitude for being able to work there,” Vella said. “It also was a nice enticement for the volunteers who work in the garden.”

For the Indian Water Commission, Vella is also helping draft a booklet about traditionally-irrigated native crops, whose proliferation could provide economic opportunities, as well as nuturitional, ecological and cultural benefits. He worked closely with a Nanüümüyadohana language speaker who shared insights about the philosophy of their culture through language. “Language revitalization and food system revitalization have a lot in common,” Vella said.

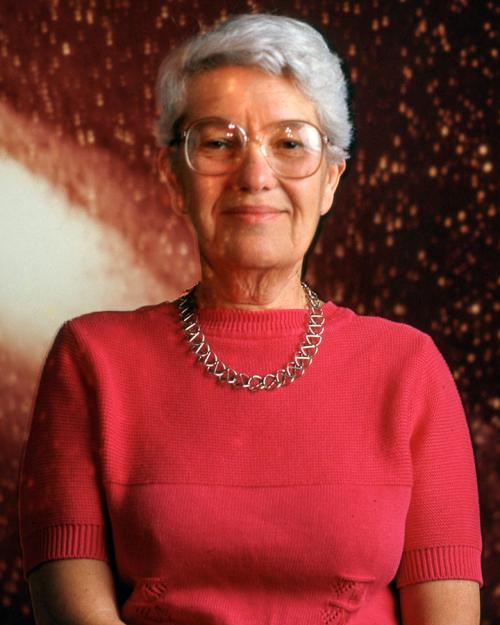

As part of his education, Vella spent two years studying at Deep Springs College, a small, remote, learning community on a cattle ranch in the Nüümü & Newe homelands of Eastern California. Students receive a full scholarship and prepare for “a life of service to humanity.” The College is associated with the Telluride House on West Campus.

Now back at Cornell, Vella’s College Scholar honors thesis focuses on the complexity of Indigenous food systems and whether scholars and activists who aren’t members of these communities can help support them. He’s reflecting on his experiences in the Nüümü context and conducting an extensive literature review to answer the question, “What does it take to re-establish a heritage cropping system?”

“I’ve learned how interdisciplinary studies and a liberal arts education have their roles even in a field like agriculture,” said Vella, who is also pursuing a community food systems minor. “One needs to understand the politics, humanities, history, media, ecology. I feel very grateful to try my hand at that through the College Scholar program, community food systems minor, Deep Springs and working alongside Nüümü friends and leaders.”