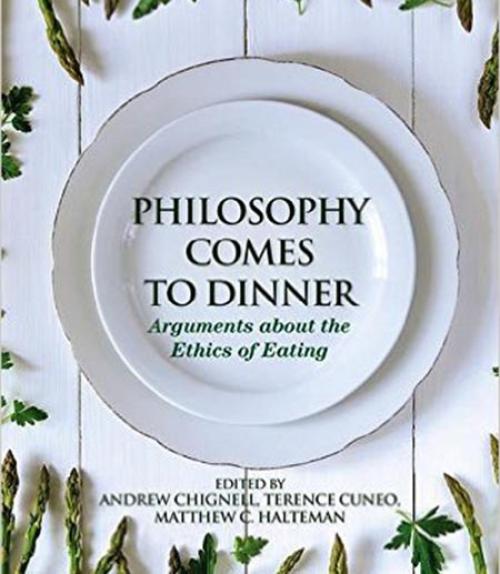

“Everyone is talking about food. Chefs and food critics have become celebrities. To state that food production and consumption are increasingly in the public eye is to understate the point,” writes Andrew Chignell, associate professor of philosophy, and his two co-editors in the introduction of “Philosophy Comes to Dinner: Arguments about the Ethics of Eating” (2016, Routledge).

Yet, they contend, while there is agreement that our eating habits and food system are in need of an overhaul, there is no clear idea about which principles should guide the discussion. Historically, philosophers haven’t often weighed in on the issue of food, they say, but one aim of their book is to show that “arguments about food are of great philosophical interest and that the conclusions of those arguments will matter to many of us.”

The book includes contributions from 15 authors on topics ranging from factory farming to artificial ingredients. Other editors are Terence Cuneo of the University of Vermont and Matthew C. Halteman of Calvin College.

Part of the book focuses on dietary ideals, explaining different dietary systems and providing practical instructions on how to live out those ideals. The other part focuses on some of the puzzling questions raised by thinking about the ethics of eating: from whether veganism is always best in a complex system such as ours, to the pros and cons of eating local.

“I really enjoyed putting this book together with my two co-editors,” Chignell said. “Most of the authors are younger philosophers who had not yet written about food, so I was curious to see the results. They did not disappoint: there are some very creative approaches here to issues concerning complicity, weakness of will, gender and artificial ingredients.”

In addition to serving as co-editor, Chignell, who co-teaches a class at Cornell called “The Ethics of Eating” that is also offered as a Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) on EdX.org, contributed a chapter to the book entitled “Can we Really Vote with our Forks? Opportunism and the Threshold Chicken.”

In that chapter, Chignell explores whether the occasional purchase of a food that’s produced by a system that a person finds morally wrong (whether because of animal mistreatment, poor working conditions or other factors) can still be morally permissible because the system itself is insensitive to slight changes in demand. He also considers situations in which someone is offered these sorts of food products for free – say, at a party or an office lunch buffet. If someone feels that the system that produces these foods is morally objectionable, what is his or her obligation in such situations?

“In teaching the course I kept hearing from students who wanted to know how they could ‘make a difference’ so I started thinking about what our obligations are when it is almost certain that our decision to consume a certain product will have no effect on outcomes,” Chignell said. “A system that produces almost 60 billion land animals worldwide is so vast and contains so many buffers and waste at every stage that the chance of making a real difference (for chickens, or workers, or whatever) is pretty slim. Once we know that, what sorts of obligations do we have?”