Nepal’s army has imposed a nationwide curfew and deployed troops to Kathmandu following two days of youth-led protests over a social media ban and political corruption, during which protesters set fire to government buildings and at least 22 people were killed.

Kathryn March, professor emerita of anthropology in the College of Arts and Sciences, has worked in Nepal for more than 50 years. She comments on the causes of the unrest.

March says:

“Things are moving very quickly in Kathmandu and many other places in Nepal so it is difficult to make clear predictions. Moreover, I am not a political theorist, but, as an anthropologist who has worked in Nepal since 1973, I see three major forces on a collision course.

“The first, and historically oldest, is what has come to be called corruption. In the early Nepal, state government functionaries were not paid a salary; instead they were given rights to extract their income from the particular function they then served for the kings: customs officers, for example, promised to convey a certain amount of money into the royal coffers and were expected to pay themselves out of whatever extra they could extract from the goods moving across their transom.

"Until very recently, the salaries of civil servants, including teachers, remained so low that many continued the practice of accepting supplemental gifts from those they were supposed to be serving. Today, the stakes of both greed and possibility have risen to the point that many people find it credible that the son of Sher Bahadur Deuba (president of the Nepali Congress Party and five times past prime minister of the country) would have been given a significant share of ownership in the Hilton Hotel that was just burned, presumably in exchange for governmental favors, quite believably in the construction and/or import licensing process.

“The second is popular discontent, especially among young people. This, again, has deep roots in long-standing tensions between Kathmandu-based elites and ordinary people. When I first began working in Nepal, this was still largely the chasm between the royal family and its retainers and the overwhelmingly rural subsistence farming peasantry. The monarchy and its friends came almost entirely from a single linguistic, religious, cultural and social group (with the innermost core being largely related by kinship and marriage). Being a “have” or a “have-not” penetrated every aspect of life, from whether you could get a government job or start a business, to getting a passport, a car, an education or a phone.

"This is not the first time these social fissures have erupted. In 1990, and again in 2006/8, in part because of increased aspirations of an emerging professional and middle class, the country was rocked by demands for more inclusive opportunities, especially from ethnic communities who constitute almost half of Nepal. These popular movements won the Nepalese people important human rights and freedoms from an absolute divine right totalitarian monarchy, but the democracy it heralded was heavily controlled by the parties and party machinery.

"To me, the striking differences from the current movement is not so much that it involves youth and the media. The earlier movements were predominantly fueled by young energy and the media, especially the then-new CNN and its need for 24/7 news, which hungrily broadcast images of Nepal's then-latest protests onto a global stage, and a young professional, especially medical, class which had access to the equally new internet to circumvent old-style media censorship. What is new this time is that the media, now social media, and the specific demands of young people are being given center stage in our understanding of what's going on in Nepal.

"The loosening of royal governmental control over people's rights to speak and move opened the floodgates of centuries of thwarted aspirations. Within 6 years, two-thirds of the young men from the ethnic Tamang community in west central Nepal, where David Holmberg and I have worked since 1975, no longer lived to work in the community -- about half had gone to Kathmandu in search of education or work, and half had gone overseas, mostly to the Gulf, but some are today everywhere around the world from Malaysia to Ithaca, New York. The impact of the remittances -- monetary, social, cultural -- they send back are immeasurable, literally: no one really knows how much more makes its way home that doesn't go through official institutions like banks, but even the official figures suggest that a staggering one-third of the Nepalese economy comes directly from abroad.

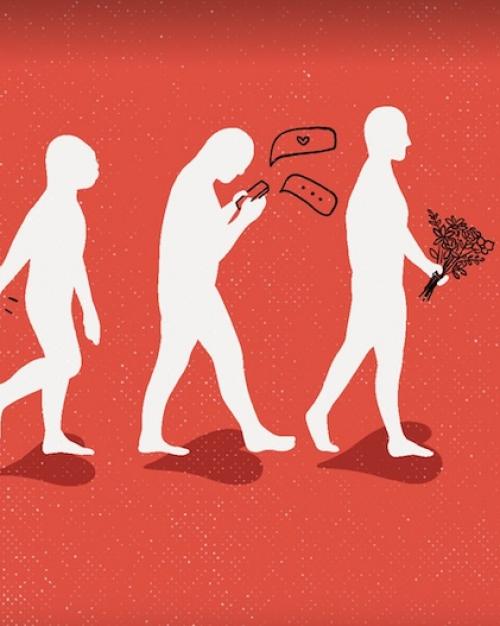

"The final force and presumptive final straw in this round of civil protest in Nepal is social media. To the displaced young people and their communities left behind, social media is a lifeline -- not only to communicate with loved ones, but to find jobs, negotiate national and international red tape, engage in business, share knowledge and kill time. Jobs, or rather the lack of meaningful jobs, in Nepal is perhaps the most important contemporary issue for Nepalese youth. With employment among youth still in the country topping 20%, this last -- known often by the English loan word expression "time pass" -- is non-trivial. The censure often expressed in the West for social media platforms like Facebook or TikTok as degraded forms of human activity compared to face-to-face relationships and other more meaningful or economically useful activities presupposes that these are in fact options. But for most young Nepalese the choice is more stark: stay at home and be unemployed, or go abroad and be lonely. In both cases, online relationships, scrolling, games, music and the pursuit of pop culture fill a new void.

"So it was stunningly unwise of the now-disgraced politicians to attempt to contain criticisms of their own attempts to grab bribes/taxes from social media by shutting them down. The fuse lit by this closure not only fired people's resentment about disparities in wealth and privilege, it ended in the burning of some of the most important sites of government rule -- notably the National Parliament Building, Singha Darbar (which houses much of the administration), and the Supreme Court, to say nothing of the Ministers' Quarters and the personal residences of many other government and party officials. It is not yet clear how much of the extensive destruction of public and private property was done by activists in the Gen-Z movement. The Gen-Z organizers deny involvement in violence, except as victims of state violence themselves on the first — from their point of view, peaceful — day of protest. But whether the destruction was the result of anger boiled over in some in the large and acephalous typing crowd or were, as some have suggested, a concerted effort on the part of other forces to delegitimize the movement, destroy evidence that could be used against the now-toppled government, or outright thugs, remains to be proven.

"It also lit up the potential power of the new media and the young people who create them. TikTok exploded with variants of "Nepo Babies" which posted widely viewed images of elite lifestyles with conspicuous displays of wealth were juxtaposed with those of struggle and poverty for most Nepalese and explicitly linked the inspiration for the Nepal protest to other international critiques of economic inequality. Straw Hat Pirate flags also waved among protesters, linking them, through the invocation of the Japanese animé figure One Piece, both to international youth gaming culture and flamboyant resistance. Other social media posts drew parallels to the effectiveness of youth movements in Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. Enough news about events in Nepal squeezed through VPNs on Facebook, X and other sites so that there was an eager global network waiting for further news, images and rumors.

“In the chaotic vacuum that all this protest, government collapse and firestorm has produced, I will be watching carefully to see who emerges from the literal ashes. Leading contenders for what is seen in many quarters as corruption- and party-free leadership are Kul Man Ghising (heroic figure who untangled corruption in the Nepalese electronic supply and eradicated crippling load-shedding), Sushila Karki (former Chief Supreme Court justice who upheld the independence of the judiciary), and Balen(dra) Shah (musician and rapper who became a popular mayor and rejuvenator of Kathmandu). There are others, including some relatively self-appointed ones. But the army is surely watching. And royalists are inevitably watching the army."