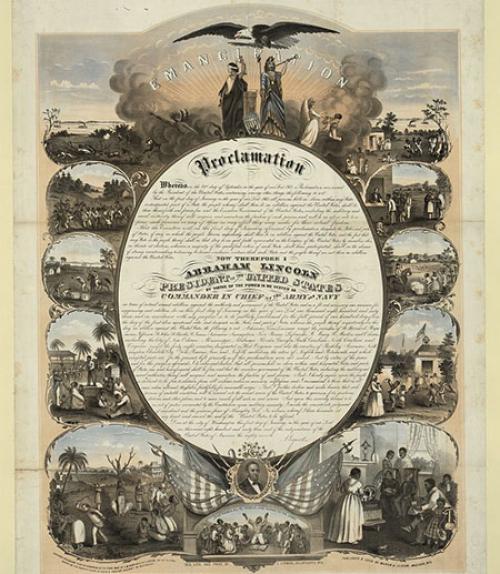

Juneteenth—June 19, 1865— marks the day when the last collective of enslaved people heard the Emancipation Proclamation in Galveston, TX, a full two years after Abraham Lincoln delivered it.

Derrick Spires, associate professor of English, studies early African American literature, culture and citizenship and is the author of “The Practice of Citizenship: Black Politics and Print Culture in the Early United States.” He says we must not forget, however, that the Proclamation excluded Kentucky, Maryland, Delaware, Missouri and parts of Louisiana and Virginia. National emancipation did not happen until ratification of the 13th Amendment in December 1865:

"We mark Juneteenth as one culminating moment in a long and violent journey to make abolition and equality the policy of the United States. And yet, we cannot forget that the Emancipation Proclamation and the 13th Amendment were not givens, that both were hotly contested, and that neither addressed the damage enslavement wrought. They were never enough.

"Even so, as soon as the Civil War ended, Black Americans convened state and national conventions to make sure they had a hand in shaping the reconstituted nation. That white Americans eventually responded to this brilliant burst of black activism with violent retrenchment should serve as a warning to us to remain vigilant, even as current uprisings yield the potential for systemic change.

"Juneteenth reminds us of at least three things: 1) the always-belated nature of freedom in the United States, especially for Black people, 2) Black citizen’s persistent determination to make democracy and justice a reality, and 3) the ongoing presence of white backlash to these efforts."

For media inquiries, contact Linda Glaser, news & media relations manager, lbg37@cornell.edu, 607-255-8942