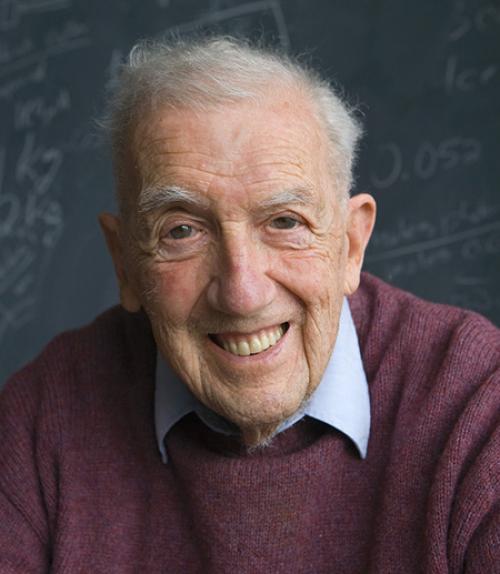

George Paul Hess, professor emeritus of biochemistry in the Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics, College of Arts & Sciences, died on September 9 at home in Ithaca. Friends and colleagues are invited to a memorial service at 2 pm on Saturday, November 7 in the chapel of Annabel Taylor Hall. A reception will follow at 3 pm in the adjoining Founders Lounge.

Hess joined the Cornell faculty in 1955 and served for 60 years. His research focused on the mechanisms of proteins investigated using fast reaction techniques, some of which he developed. Initially, he investigated proteins in solution, including the enzymes alpha-chymotrypsin, lysozyme, and cytochrome c. He then turned to the structure and function of membrane-bound proteins, particularly neurotransmitter receptors that facilitate communication between the cells of the nervous system. Malfunction of these receptors is the key to many neurological diseases, and the proteins are the targets of many clinical therapies as well as abused drugs. Rapid reaction techniques to examine receptor proteins embedded in a cell membrane were not available prior to his work.

Under his leadership, Hess’ group developed new techniques and chemical probes to study the receptors in single cells on sub-millisecond time scales. The innovative approach included a laser-pulse photolysis method that allows researchers to measure rate constants for individual steps in the mechanism of action of the receptor. For this accomplishment, his group also developed compounds (“caged” neurotransmitters) that can be equilibrated with the receptors but remain biologically inactive until photolyzed to release the neurotransmitter very rapidly. In this way, the delay due to the time needed for the reactants to reach an initial equilibrium was overcome. He combined this method with electrophysiological techniques developed in other laboratories. Using the new approaches, the group has illuminated how mechanisms of receptors are affected by therapeutic and abused drugs, or by epilepsy-linked mutations, and they have worked to identify compounds that alleviate the receptor malfunction.

“George Hess was a pioneer in the study of a class of proteins called ion channels, gate-keepers that allow specific small molecules to enter cells,” said colleague Volker Vogt, Cornell professor of molecular biology and genetics. “His studies combined chemical and biological approaches to provide an unprecedented mechanistic understanding of this process, which is the basis of the action of nerves.”

“George had a mind and a physical constitution that could not be ignored,” added Barbara Baird, senior associate dean in the College of Arts & Sciences and professor of chemistry and chemical biology. “Whether in scientific discussions or the great outdoors, a strenuous hike for others was an enjoyable walk in the woods for him. I and many others will miss his invigorating friendship.”

George Hess was well known for his mentoring of undergraduate, graduate and postdoctoral students, and he twice received Outstanding Educator Recognition by Merrill Presidential Scholars.

Hess was a member of the National Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and a fellow of the Biophysics Society, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and the American Academy of Microbiology. He was a John S. Guggenheim fellow, a Fulbright senior research scholar, a special fellow at the National Institutes of Health, a Fogarty scholar and a recipient of the Alexander von Humboldt Award.

“George had such a tremendous impact in science, and in my own scientific journey,” said colleague Linda Nicholson, professor of molecular biology and genetics. “He was so generous in spirit, and would regularly drop by my office to say hello and to discuss science and life. His visits were often filled with stories of his own journey, from his boyhood in Austria and California, to his various adventures as he grew from a young scientist into a world-renowned member of the National Academy of Sciences.”

Hess was also a visiting fellow and visiting professor at many universities around the world during his career. He served twice as a U.S. Department of State cultural exchange professor in Europe; he was on the advisory board of the Center for Molecular and Behavioral Neuroscience in Puerto Rico. He served on numerous review panels and the Editorial Advisory Board of Biochemistry.

Hess received his bachelor and doctoral degrees in biochemistry from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1951, followed by a postdoctoral position in chemistry at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. At Berkeley with C. H. Li, he showed that the adrenocorticotropic hormone, thought to be a protein, is actually a small peptide adsorbed to a biologically inactive protein. At MIT in John Sheehan’s laboratory, he developed the dicyclohexylcarbodiimide method for the formation of peptide bonds.

In 2012, the Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics hosted an academic seminar to celebrate his work and career.

“I greatly admired the scientific partnership between George and his wife, Susan,” said Eric Alani, professor and chair of the Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics. “This interaction, in addition to the beautiful science that it led to, provided us with a wonderful example of the importance of collaboration in all aspects of one’s life.”

George Hess was born in Vienna, Austria to the late Henry and Edith Mueller Hess, and came to the United States in 1938. He served in the United States Army from 1944 to1946. George Hess is survived by his wife of 35 years, Susan Coombs ’80, and four sons, Peter, Richard, Paul, and David and daughters-in-law Natalie Mahowald, Chris Colbath-Hess, Katherine Childs, and Andrea Kahn, and his eight grandchildren, Gabriel, Noah, Jacob, Alan, Sophie, Elias, Rowan, and Lyndon. In addition to his parents, he was also predeceased by his daughter, Alvis Wieder, and his first wife, Jean Ray, and is survived by his second wife and mother of his sons, Betsey Williams. His son Peter Hess ’79 is a professor of biological and environmental engineering at Cornell, and his daughter-in-law Natalie Mahowald is a Cornell professor of earth and atmospheric sciences.