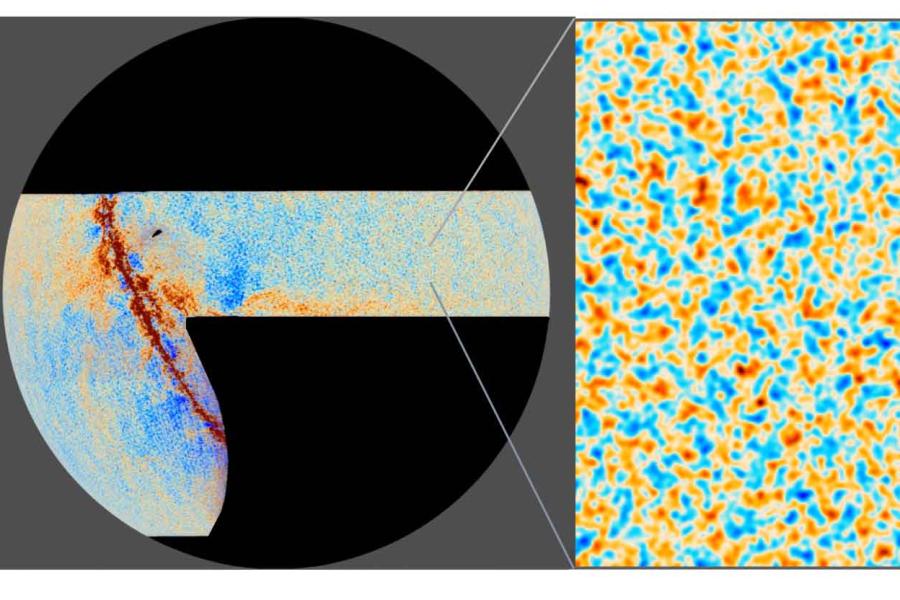

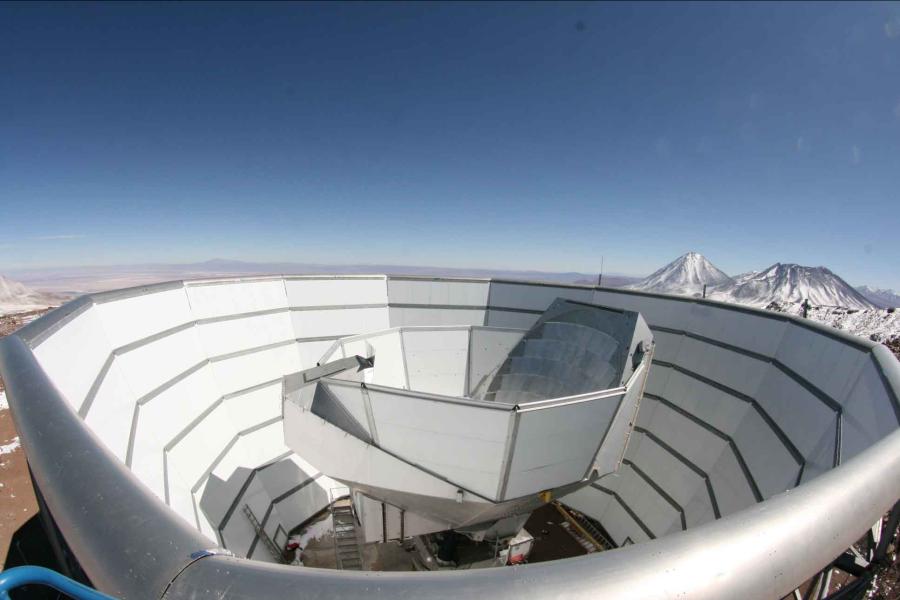

New research by the Atacama Cosmology Telescope (ACT) collaboration has produced the clearest images yet of the universe’s infancy – the earliest cosmic time yet accessible to humans. Measuring light that traveled for more than 13 billion years to reach a telescope high in the Chilean Andes, the new images reveal the universe when it was about 380,000 years old – the equivalent of hours-old baby pictures of a now middle-aged cosmos.

The new results confirm a simple model of the universe and have ruled out a majority of competing alternatives, says the research team. The work has not yet gone through peer review, but the researchers will present their results at the American Physical Society annual conference on March 19 and have submitted papers with their findings. The new ACT data are also shared publicly on NASA’s LAMBDA archive.

“It's thrilling to see these new precise cosmological results, which are the culmination of over two decades of research with ACT. These measurements are the state-of-the-art cosmic microwave background (CMB) measurements covering about half the sky, enabled by critical support from the National Science Foundation,” said Michael Niemack, professor of physics and astronomy in the College of Arts and Sciences and a member of the research collaboration for the last 20 years. He helped design the telescope optics and build, test, deploy, and operate the low temperature detector and optical technologies that were used in all three generations of instruments on ACT.

In the first several hundred thousand years after the Big Bang, the primordial plasma that filled the universe was so hot that light couldn’t propagate freely, making the universe effectively opaque. The CMB represents the first stage in the universe's history that we can see – effectively, the universe’s baby picture.

The new images give a remarkably clear view of very, very subtle variations in the density and velocity of the gases that filled the young universe. The polarization image reveals the detailed movement of the hydrogen and helium gas in the cosmic infancy, which tells researchers about how strong gravity pulls in different regions of space.

What look like hazy clouds in the light’s intensity are more and less dense regions in a sea of hydrogen and helium – hills and valleys that extend millions of light years across. Over the following millions to billions of years, gravity pulled the denser regions of gas inwards to build stars and galaxies.

These detailed images of the newborn universe are helping scientists to answer longstanding questions about the universe’s origins.

"ACT was an incredibly fun experiment and a welcoming, supportive collaboration to be part of. It’s exciting that the hard work of so many people has led us to this point,” said Yuhan Wang, a postdoctoral research associate in the Cornell Laboratory for Accelerator-based ScienceS and Education. Wang has collaborated widely on the research, including the last instrument upgrade for ACT, as well as its decommissioning in 2022. He is a lead author on one of the forthcoming papers on the research results.

According to ACT’s measurements, the observable universe extends almost 50 billion light years in all directions from Earth, and has as much mass as nearly 2 trillion trillion Suns, or 1,900 “zetta-suns.” Of that mass, normal matter – the kind we can see and measure – makes up only 100 zetta-suns. Another 500 zetta-suns of mass are mysterious dark matter, and the remaining mass is made up of the dominating vacuum energy (called dark energy) of empty space.

Of the normal matter, three-quarters of the mass is hydrogen, and a quarter helium, which was produced in the first three minutes of “cosmic time” after the universe was born. The elements that humans are made of – mostly carbon, with oxygen and nitrogen and iron and even traces of gold – were formed later in stars.

ACT’s new measurements have refined estimates for the age of the universe and how fast it is growing today. The infall of matter in the early universe sent out sound waves through space, like ripples spreading out in circles on a pond. The new data confirm that the age of the universe is 13.8 billion years, with an uncertainty of only 0.1%.

“The results set the stage for our upcoming major research projects — Simons Observatory and CCAT Observatory. The Simons Observatory Large Aperture Telescope will directly improve on the ACT results by making more sensitive measurements over a larger fraction of the sky, and CCAT Observatory's Fred Young Submillimeter Telescope extend these measurements to shorter submillimeter wavelengths enabling a wide range of exciting new astrophysics research,” said Niemack.

In recent years, cosmologists have disagreed about the Hubble constant, the rate at which space is expanding today. Using their newly released data, the ACT team has measured the Hubble constant with increased precision. Their measurement matches previous CMB-derived estimates.

A major goal of the work was to investigate alternative models for the universe that would explain the disagreement about the Hubble constant, such as new ways for neutrinos and the invisible dark matter to behave. But the ACT study showed no evidence of new particles or fields in the early universe, thus reaffirming the standard model of cosmology with extraordinary precision.

“I find it very interesting that with the latest ACT data we found that there is no statistical preference for extensions to the standard cosmological model. In fact, these results place very tight constraints on such alternative theories,” said Nicholas Battaglia, associate professor of astronomy (A&S). In his 15 years on the project, he has worked on numerous aspects of data analysis, theory, simulations, calibration and analysis.

Other Cornell researchers in the ACT collaboration include Rachel Bean, the Jacob Gould Schurman Professor of Astronomy and Senior Associate Dean for Math and Science (A&S).

ACT completed its observations in 2022, and attention is now turning to the new, more capable, Simons Observatory at the same location in Chile, for which Niemack helped design the CMB detector arrays.

The ACT research was supported by the National Science Foundation, Princeton University, the University of Pennsylvania, and a Canada Foundation for Innovation award. The project is led by Princeton University and the University of Pennsylvania, with 160 collaborators at 65 institutions. ACT operated in Chile from 2007-2022 under an agreement with the University of Chile, in the Atacama Astronomical Park.