When Rolf Barth ’59 thinks about his time as a Cornell Chemistry major, he remembers the 80 hours a week he spent in classes, labs, his language courses in German and Russian, plus three summers doing research at CalTech and Scripps Oceanographic Institute.

“At Cornell, they emphasized spoken language from the very beginning, so that while you started the year with basic conversation, by the end of the year you were carrying out complicated and lengthy conversations,” he said. “I still use the German and Russian almost every day,” especially the latter since he is now working on a paper relating to Joseph Stalin’s mysterious death.

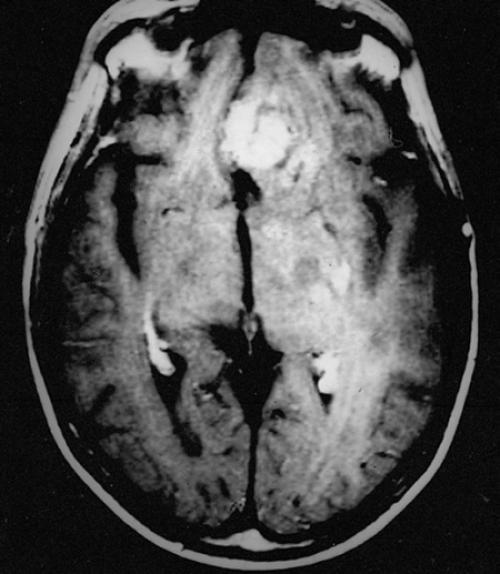

Barth has taken that rigorous Cornell chemistry training and flourished as a physician scientist, with a career focused on innovative ways to treat brain cancers, including glioblastoma (GBM), the type that resulted in Sen. John McCain’s death.

An academy professor in the Department of Pathology at The Ohio State University and a University Distinguished Scholar, Barth has been involved in radiobiologic and radiotherapeutic research for almost 40 years. He is a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, author of more than 370 scientific publications — including his first at the age of 19 with Nobel Prize winner George Snell —and has more than 12,000 citations to his credit.After medical school at Columbia University’s College of Physicians & Surgeons, a surgical internship at Columbia and a postdoctoral fellowship in Sweden, he went on to the National Institutes of Health as a research associate in the Laboratory of Immunology and then a pathology resident at the National Cancer Institute before joining the medical faculty at the University of Kansas in 1970, becoming a full professor in six years.

This was followed by two years in private practice in Milwaukee with academic appointments as a clinical professor of pathology at the Medical College of Wisconsin and the University of Wisconsin in Madison. In August 1979, he joined the Department of Pathology at The Ohio State University, and shortly thereafter he met Albert Soloway, a well-known boron chemist and cean of the College of Pharmacy.

“Soloway had been working on Boron Neutron Capture Therapy (BNCT), which I had never heard of before. In theory, it provides a way to selectively destroy cancer cells and spare surrounding normal tissue, making it an ideal type of radiation therapy. It sounded so interesting that I decided that this would be a good area for my research on tumor targeting. Dr. Soloway and I became good friends,” Barth said, adding that the pair have had numerous research grants together and have authored more than 100 publications together related to BNCT.

“We are trying to help patients who have cancers like John McCain’s glioblastoma,” Barth said. “These are the most difficult cancers to treat for a variety of reasons.” Patients with these cancers receive surgery and chemoradiotherapy, but the results are not good. According to the American Cancer Society, patients diagnosed between the ages of 20 and 44 face a 19 percent chance of survival five years after diagnosis; among those 45 to 54, that drops to 8 percent; and for people 55 to 64, the five-year relative survival rate is only 5 percent.

“The idea was that BNCT could be a way to help these patients, but that has turned out to be much more complicated than we thought,” Barth said, first because of the requirement that the boron drug must be delivered to every cancer cell and second, a sufficient number of neutrons are needed to kill the cells. Until recently, specially designed nuclear reactors have been the source of these neutrons, but now accelerators that can be more easily sited in hospitals are being evaluated.

BNCT treatment also has been used to treat patients with recurrent tumors of the head and neck region and melanomas in difficult-to-treat areas. Although BNCT has resulted in some improvement in survival, Barth said that it is not curative for patients with malignant brain tumors. However, for patients with other types of cancer such as head and neck tumors or melanomas, the results have been more promising.

For Barth, the possibility of providing a new treatment for patients who have tried everything else continues to motivate his work.

Even though Barth is now a professor emeritus, he remains active in his research and academic activities, with three papers relating to BNCT recently published in “Cancer Communications” and trips to China and Taiwan planned for this fall to present his research at conferences and meetings.

His focus on pathology also has led to a few interesting side projects, scouring historical pathology and autopsy reports to look into the actual causes of death of some famous leaders – Stalin (who Barth concludes died of a massive stroke and complications secondary to it, and not from “poisoning,” as some have speculated) and Sun Yat-sen (who died of gallbladder cancer, not liver cancer, as had been widely reported in the press).

When you ask Barth about his greatest accomplishments, however, he doesn’t gush about his multiple papers or citations. He’ll talk about his four children, who have all made names for themselves in various fields of medicine and science. “Those other honors are all really minor,” he said, adding that none of them would be possible without the support of his wife of 53 years, Christine.