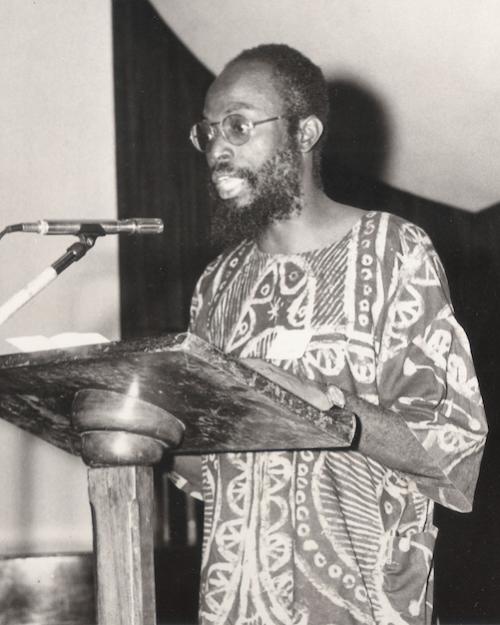

Derrick R. Spires, associate professor of English, was awarded the St. Louis Mercantile Library Prize for his book “The Practice of Citizenship: Black Politics and Print Culture in the Early United States."

The award, which is given by the Bibliographical Society of America, honors research in the bibliography of American literature and history. It carries a prize of $2,000 and a year’s membership in the organization.

“It was really validating for people who are a part of my target audience to recognize the value and usefulness of the book and what it does,” Spires said.

Through his book, Spires “reveals the degree to which concepts of black citizenship emerged through a highly creative and diverse community of letters,” according to its summary.

During his research, Spires found a series of documents published by black writers around 1808. These addresses on the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade routinely began with the phrase “fellow citizens.” State and national conventions held by African Americans from the 1830s onward also issued addresses to “fellow citizens.”

The phrase prompted Spires to ask himself, “On what basis could African Americans claim citizenship?” Before the 14th amendment, he said, there was no standard federal definition of who was and wasn’t a citizen.

“If you start thinking about citizenship as what people do, rather than [who they are], you start seeing citizenship happening all over the place,” Spires explained. “People who see someone in need, and they go to meet that need, that is someone behaving as a citizen.”

Much of Spires’ work focuses on uncovering and showcasing history from a different perspective.

“Assume that if there is a thing to be done, in terms of citizenship, in terms of humanism, in terms of art, assume that there were black folks in this space doing it, and doing it well,” he said.

Looking forward, Spires has become fascinated with what he describes as 19th century black “social media,” referring to a collective of black writers who wrote under pseudonyms to and about each other.

The pseudonyms, Spires explained, were not “necessarily hiding identities.” Instead, they functioned like Twitter handles.

“It looks a lot like social media,” he said.