Kanzi the bonobo (pygmee chimpanzee) hunches over, banging the rock in one hand against the rock in his other hand, determinedly whacking it until a piece slices off: making and using the same kind of tool as our Stone Age ancestors.

The scene from that video, and others showing Kanzi’s language abilities, opened “Eloquence of the Apes: a Trans-Disciplinary Workshop on Apes, Language and Communication,” held Oct. 20-21 at Cornell and featuring primatologist Sue Savage-Rumbaugh and her research.

The workshop examined questions related to apes, language and communication, bringing researchers from multiple disciplines to examine and re-assess the language of our closest relatives, encompassing orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos, and modern humans and their fossil ancestors.

An unusually high percentage of students, both graduate and undergraduate, attended the workshop, indicating the high interest from many fields in this area of study, said organizer Laurent Dubreuil, professor of Romance studies, comparative literature and cognitive science.

“Our goal is to open up a new space for intense conversation between humanists, social scientists, and scientists,” said Dubreuil. “The emerging fields of ‘post-humanities’ and ‘animal studies’ are engaged in a wide re-assessment of sciences and technologies, while many new and exciting developments at the crossroads of the sciences are currently re-interpreting the diverse facets of human (and animal) culture that have traditionally been explored by the humanities.”

New Collaborations

The enthusiasm at the workshop is carrying over into new collaborations – even, perhaps, a cross-disciplinary institute for language studies or the origins of culture, said Dubreuil. “Not just about chimps and bonobos. After all, we’re apes too.”

Dubreuil and Savage-Rumbaugh are working on a book, “Dialogues and the Human Ape,” that explores philosophical big-picture questions such as what is human, what is ape and what is the nature of thought. The book is scheduled to be released next year by the University of Minnesota Press.

Another collaborative project will create video testimonies of people who have worked with the apes. According to Cathy Caruth, Rhodes Professor in the Humanities and a specialist in trauma studies, video testimonies are a genre arising partly out of work with Holocaust survivors. Caruth is collaborating with Dubreuil on the project.

In connection with the workshop, Morten Christiansen, professor of psychology and cognitive science, is co-teaching a class with Dubreuil this fall titled Culture, Cognition and the Humanities. Cross-listed in neurobiology and behavior, comparative literature, psychology, and cognitive science, the class points the way toward the new field that can develop from the interface of these different modes of inquiry, said the instructors.

The class and workshop both draw on the video archive recently donated to the Cornell Division of Rare Books & Manuscripts by Savage-Rumbaugh, which includes more than 300 hours documenting her experiments with apes from the late 1970s to the early 2000s. Most of these hours of interaction of language and behavior haven’t yet been studied. The rich resources invite investigation from varied fields, said Dubreuil, including history of science, psychology, linguistics and philosophy of mind.

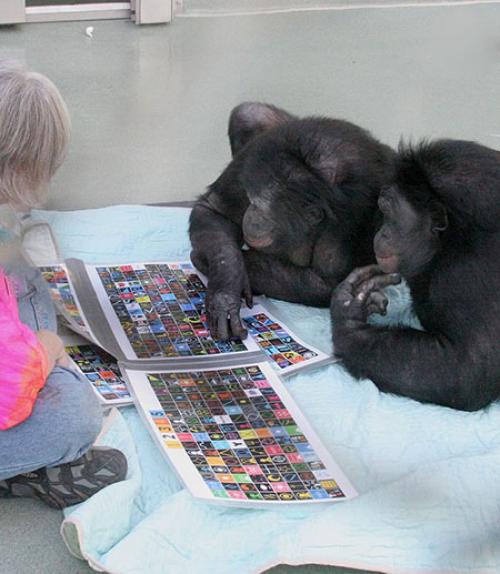

Panbanisha, a bonobo, uses lexigrams on the keyboard to communicate. Note the specific use of "yes" as an intensifier. At the beginning of the clip, Panbanisha begins an interaction by saying "chase outdoors" using the keyboard. (Posted with permission of Sue Savage-Rumbaugh)

“The monotheistic and parochial view of humans as being outside of the animal kind is no longer tenable,” noted Dubreuil in his introductory talk at the workshop. “Language, apes and communication sit at the crossroads of humanities and the sciences.”

The bonobos with whom Savage-Rumbaugh worked understand spoken English at a high level of proficiency – in one video she verbally instructs Kanzi to light a fire with the lighter in her pocket, and he takes the lighter out and starts the fire.

But the bonobos do not themselves speak English. They communicate using a set of arbitrary symbols, “lexigrams.” Most of the bonobos in Savage-Rumbaugh’s project know as many as 300 lexigrams, and although they are normally used on an electronic panel, the bonobo sometimes draw them as well.

Savage-Rumbaugh, trained as an experimental psychologist, began her work with apes and language in order to help developmentally challenged children who had failed to acquire language do the same. It soon became clear to her, she said, that the traditional approach to teaching apes to communicate was fundamentally flawed. Language, as Dubreuil noted in his talk, is about dialogue, not conditioned responses.

“A social relationship of playing, tickling, grooming and sharing food preceded the linguistic relationship about these things with the apes,” explained Savage-Rumbaugh. “Linguistic relationships always have a quality of ‘aboutness’ about them. They are sets of behaviors that are ‘about’ other potential behaviors, both linguistic and nonlinguistic.”

Savage-Rumbaugh said her experimental method can be summed up in her informal motto, “science is in the rearing.” She immersed the apes in the same kind of language-rich, interactive environment that humans are raised in, with intensive human interaction and the need for meaningful communication. Savage-Rumbaugh described it as “trying to help apes understand humans and humans understand apes.”

Drawing, fire, language and stone tools are considered the “suite” of characteristics that signaled either the appearance of language or perhaps the arrival of a new species. The bonobos Savage-Rumbaugh worked with have demonstrated all of these abilities after seeing them modeled.

In the 1990s, paleo-anthropologists Nick Toth and Kathy Schick taught Kanzi the bonobo to produce stone tools using techniques that were adopted by our early ancestors. In this 7-min excerpt, primatologist Sue Savage-Rumbaugh is using language to encourage Kanzi to produce a certain number of tools—seizing the opportunity to consolidate his counting capacities. Near the end of the excerpt, Kanzi is trying to vocalize some numbers. (Posted with permission of Sue Savage-Rumbaugh)

“We now know that our brains are not only very plastic, but that they grow new neurons at a rapid rate,” said Savage-Rumbaugh. “Humans start behaving in new ways because of cultural changes.” Because bonobo share 99 percent of their genome with humans, their nervous systems are equally flexible.

The workshop sessions were divided into three themes: evolution and origin of communication in human and non-human primates, what language brings to apes and the apes and the humanists. Cornell presenters included Dubreuil, Christiansen and Barbara Finlay, Kenan Professor Emerita of Psychology.

The breadth of approaches by workshop speakers illustrated the new ways of looking a language at Cornell and elsewhere. Christiansen spoke about “Language Evolution through the Bottleneck: From Milliseconds to Millennia,” arguing that “linguistic structure is a product of cultural evolution, not biological adaptation.” He advocated for uncovering the constraints on language that work across evolution, acquisition and processing. He pointed to the “Now or Never Bottleneck” as a key constraint on language and that “chunking” has played an important role in shaping the evolution, acquisition and processing of language. (“Chunking” is a basic memory process that allows the brain to group linguistic input into increasingly abstract representational formats, from phonemes to syllables, to words, phrases and beyond.)

Christiansen suggested looking at language use by apes from the point of view of chunking, using new computational models to analyze the data. From what he’s seen of the research, the apes’ utterances may be consistent with human chunking, he said.

Finlay spoke on “Human Eloquence Arising in a Unique Ape Life History.” Human exceptionalism, she said, arises not from brains or longevity, but from the timing of birth and weaning, menopause and fertility. “Humans are the only primate with extended longevity after reproduction,” she said. “But progress through the maturational schedule, including milestones in brain mass, does not differ between humans and other primates, when estimated from conception.”

The Apes and the Humanists

The concluding roundtable, “The Apes and the Humanists” featured humanists and social scientists, including Caruth; Peter Gilgen, associate professor of German studies; and Sonia Ragir (professor emerita of anthropology, animal behavior and conservation, Hunter College, CUNY).

In her remarks, Caruth drew on her work with trauma and human vulnerability. She noted that the growing field of trauma studies offers one perspective on non-human communication; the question of speechlessness is a significant one in trauma work. “Some suggest that the problem of speechlessness may be related to problems of listening,” Caruth said, using the example of Holocaust victims being spoken of as “not human.”

“If humans are treated as if not human addressees, the way animals are treated, then perhaps a kind of address can be established between animals and humans precisely from this site of vulnerability, this site of non-addressability that they share,” said Caruth. “I believe that Sue [Savage-Rumbaugh] communicated with the bonobos from that vulnerable site.”

Caruth also noted that literary critics and theorists speak about the rhetorical gesture common in poetry of “giving face” to an absent or dead entity. “What if we don't simply ‘anthropomorphize’ animals when we speak of their abilities to use human language, as some argue, but rather receive our faces from them, or through our interaction with them— a kind of co-constitution, perhaps?” she asked.

Gilgen addressed the longstanding question of whether animals suffer, in order to question the practices of domination and imprisonment of our closest biological relatives. For example, when apes do not respond during experiments, is it because they are not “in the mood”?

Perhaps ape language too, has been misunderstood, said Gilgen. “Linguists and philosophers of language since the 18th century have been adamant about excluding apes’ ‘innate expressions’ of pain and suffering from the realm of language proper and of symbolic systems. However, there is now plenty of research that would force us to rethink this simple opposition and instead postulate a theory of gradations.” For example, some monkey species have distinct warning calls – the warning for an approaching leopard is different from that for a bird of prey.

Returning to the question of suffering, Gilgen described a video of an old, dying chimpanzee who was non-responsive until her old caretaker, biologist Jan van Hooff, visited her. “What ensues is so heart-breaking and magnificent that this video alone should make us rethink our approach to the eloquence of the apes,” said Gilgen.