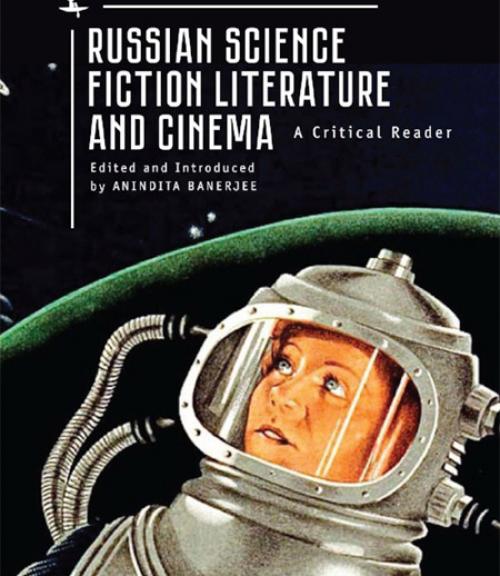

Sputnik proved a game changer for science fiction in Russia, merging science fiction with science fact. A new volume edited by Anindita Banerjee, “Russian Science Fiction Literature and Cinema: A Critical Reader,” examines Russian science fiction and its impact on global culture.

“In Russia perhaps more than anywhere else, science fiction served as the battleground for competing attitudes toward not just science and technology but the very idea of their role as the engines of modernity,” writes Banerjee, associate professor of comparative literature. “Sputnik’s impact – crossing the boundaries of private life and public culture, domestic enthusiasm and international curiosity, technological spectacle and participatory entertainment, contemporary aspirations and historical visions, and, last but not least, the diverse media of print, film, radio and television – played an instrumental role in transforming science fiction from Russia into a serious object of study.”

The book is arranged in chronological order, reflecting major shifts in history and culture. The first section, “From Utopian Traditions to Revolutionary Dreams,” emphasizes what Banerjee calls Russia’s “governing obsession” from the 18th century and beyond: “how to power the future in both the material and the ideological senses.” One of the articles, “Generating Power,” is a reprint of a chapter from Banerjee’s book “We Modern People: Science Fiction and the Making of Russian Modernity.”

The second section focuses on “Russia’s Roaring Twenties,” which produced some of the most famous and most controversial science fiction in the wake of the October Revolution. The third section looks at a time “From Stalin to Sputnik and Beyond,” which Banerjee writes challenged the view “that the utopian aspirations of earlier decades had gone into complete hibernation during the Stalin years.”

The book’s concluding section, “Futures at the End of Utopia,” encompasses the disillusionment of the present and nostalgia for the futures previously dreamt of.

The collection has an archival component, with the goal of retrieving the best articles and reconstructing the history of scholarship on this topic, said Banerjee. For example, the first essay in the volume, written in 1971 by Croatian-born literary theorist Darko Suvin, is arguably the first academic work on Russian science fiction published in English; Suvin became a founding figure of the field of science fiction studies worldwide.

Because science fiction is told across multiple platforms and formats from print and photography to analog and digital media, the book gives equal attention to literary and cinematic study, said Banerjee. Fewer than half of the book’s essays are by scholars in Slavic studies; historians of science and technology, scholars of cinema studies and members of the film industry among others offer a wide range of perspectives. The essays in the book are also transnational in scope. As Banerjee noted, linguistic traditions are not isolated but operate within the global arena, and she was concerned with issues that transcend one place and time.

Banerjee has a second edited volume on science fiction forthcoming. “Science Fiction Circuits of the South and East” focuses on world science fiction (not written in English) that resulted from cultural exchanges between formerly socialist and colonial countries.

Linda B. Glaser is a writer for the College of Arts and Sciences. This article also appeared in the Cornell Chronicle.