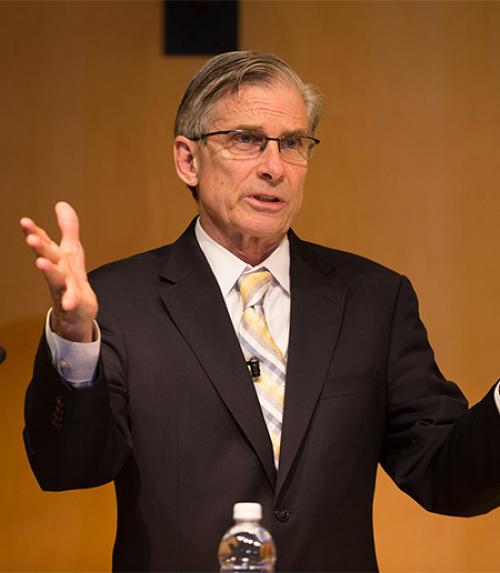

We are living through an “extended moment of making fun of philosophers” in America, according to National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) Chair William D. Adams, who spoke on the past and future of the humanities in Klarman Hall auditorium Feb. 24.

Adams said a presidential candidate boldly and unapologetically stated in a recent debate that our country needs more welders than philosophers. But Americans, Adams argued, should not forget that our nation was founded by highly educated people who debated constitutional values in “one of the great public humanities moments in the history of the United States.” Others joined the chorus of debate in newspapers. We are still “literally drowning in issues that have fundamental philosophical significance,” Adams said. He argued, “The world is constantly presented with these challenges that can’t be addressed – let alone solved – without the forms of knowledge and understanding that are fundamental to humanistic work, scholarship, teaching and learning.”

Adams said more people go to museums in the United States per year than to all professional sporting events and amusement parks combined, which drew a “whoop” of support from the audience. But concurrently there is enormous pressure on the humanities in academia, made manifest by downward trends in course enrollment, fewer undergraduate majors and fewer teaching positions.

“In the public sphere,” Adams said, “we’re seeing a lot of public skepticism about the worth of the humanities in the context of our current social, economic and political lives.” Just yesterday, he said, it was reported that the governor of Kentucky is advocating differential pricing for degrees based on their presumed use to society – with engineering degrees being cheapest and humanities most expensive. This is a moment of increasing pressure for the field, he said.

What is the solution? Adams said that scholars need to re-engage in new ways in the public realm, writing work that is accessible to the public. To that end, NEH started a Public Scholar Program in 2015.

Adams also advocated restructuring the undergraduate humanities curriculum, including training students for citizenship – deep “participation readiness” that goes beyond voting. The NEH is launching “Humanities Connections” to support universities to renovate their curricula.

Adams advocated moving away from teaching undergraduates using traditional graduate subspecialties, but he also argued for a shift in graduate training itself. Since only about 60 percent of humanities graduate students secure tenure-track teaching positions, their education must include training for careers beyond the academy. When pressed, Adams indicated he is unsure what this new training paradigm would look like.

A further direction for the humanities is to collaborate with STEM fields in teaching areas of common interest, such as medical ethics. In medical schools, Adams noted, a key dimension of study is how human patients experience the world. An audience member expressed concern that the future of humanities seems to be serving as handmaiden to something else, rather than being an end in itself.

The National Endowment for the Humanities has supported 63,000 projects in academia and the public square in its first 50 years, for a total of $5.3 billion. An additional $2.5 billion was matched by challenge grants. Cornell’s share is 360 grants, valued at $25 million. These funds have helped to build what Adams calls a “humanities ecosystem” throughout the country, comprising universities, libraries, museums, historic sites, cultural organizations, radio, television and film.

The lecture was presented as part of Cornell’s Society for the Humanities’ annual Future of the Humanities lecture and marked the 50th anniversary of the NEH and the Society for the Humanities.

Amanda Bosworth, a Cornell doctoral student in history, is a writer intern for the Cornell Chronicle.

This article originally appeared in the Cornell Chronicle.