This is an episode in the “What Makes Us Human?” podcast from Cornell University’s College of Arts & Sciences, showcasing the newest thinking from across the disciplines about what it means to be human in the twenty-first century. Featuring audio essays written and recorded by Cornell faculty, the series releases a new episode each Tuesday through the fall.

How can a theoretical chemist, who has spent all his life calculating the preferred shapes of molecules and their reactions, how can he tell us something about what it means to be human? Of course I’m all too human; I even write poetry and like poppy seed cake too much. But I can’t point to a single molecule that has benefited humanity that has come directly from my work.

Let me tell you a story, self-serving as it might be, which gets at what being human means to this chemist. A dozen years ago, I gave a seminar at the University of Akron in Ohio. Gerald Koser, a very good polymer chemist there, asked me what I thought of a hypothetical “iodabenzene” molecule. The name immediately evoked benzene, an icon of organic chemistry. Chemists have been studying benzene and its relatives for over 150 years. Thomas Pynchon, Cornell graduate, his book Gravity’s Rainbow can tell you a little more of the remarkable story of benzene. Iodabenzene, which would be similar to benzene but with a slightly different make-up, just one carbon and hydrogen in benzene substituted by an iodine (ergo the ioda- moniker), nothing to do with Star Wars. Iodabenzene did not and does not (yet) exist.

But could it?

I said to Koser, “That molecule is in trouble.” Koser knew why I said what I did, and I knew Koser knew I knew. Because we shared a common background. For nearly 90 years we have been aware that in benzene, having 6 so-called π electrons – which describe a particular kind of bond between atoms, nothing to eat – that this is good and having two more π electrons past the six is bad. And we knew both of us that iodabenzene would have 8 π electrons.

“We’ll look at it,” I told Koser.

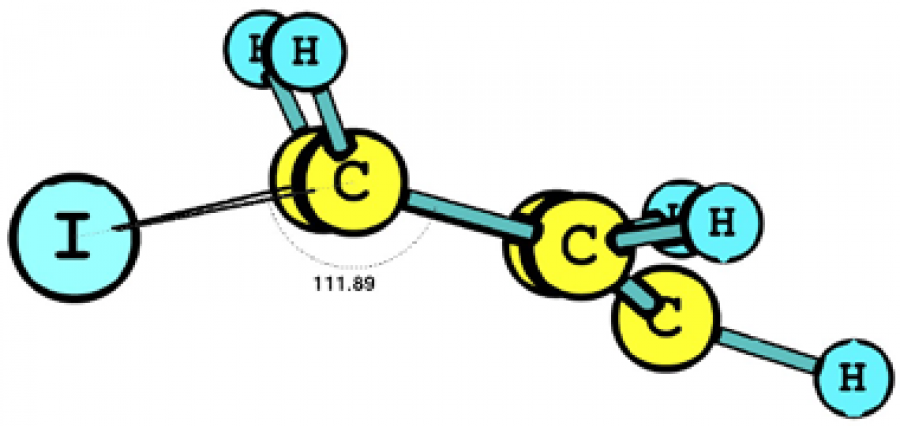

Trouble, iodabenzene’s kind of trouble, is a challenge. It took a while. Finally, eight years ago a talented young Jordanian chemist, Abdel Rawashdeh, came to Cornell. Using a computer to do his intensive calculations, he found out something important about the shape of the hypothetical iodabenzene; this molecule did not want to be flat. “Want” that, of course, is an anthropomorphic way to talk about molecules. We started to call the structure that emerged for the molecule a “bird,” because that’s the way it looked. Now, professional gatekeepers – we have them too, the editors of our journals – they didn’t like either term, but I think anthropomorphisms are a good way to describe life.

Abdel went back to Yarmouk University in Jordan. But the job was not done.

But I am patient. In 2016 a new postdoctoral associate from India, Priyakumari, who calls herself Priya, joined the group, and took on the study. We felt that iodabenzene went into the bird shape to avoid the trouble the 8 π electrons gave it. Of course we were not interested in gaging the misery of the molecule, to which detailed calculations testified -- that would be somewhere between boring and sadistic. But iodabenzene’s trouble with its π electrons made us think of a class of molecules known from the 19th century, called Meisenheimer complexes. And we knew that a strategy exists, has existed for many years, for stabilizing these Meisenheimer complexes, a way to substitute some atoms in the molecule. Computer calculations confirmed our intuition that this strategy also worked for iodabenzene.

What does this small chemical story have to do with being human? To be human is to try to understand. Simulations – that’s what our computer was doing for us – that’s not understanding. Yes, human ingenuity and understanding built those PC cores on which we compute. And there is still more human creativity in the software we share.

But numbers do not constitute understanding. It was Gerald Koser and I who asked the question, “What is wrong with this molecule?” It was Abdel and Priya and I who made the computers part of our humanity, as we sought an answer, who formed a conversation with the human imagination out of those numbers flitting across a display. We reasoned, in a contemporary way, a state of the art way, using quantum mechanics, buy still in ways rooted in the past (remember those 19th century Meisenheimer complexes?). We reasoned in words and images and chemical structures. And, inspired by likenesses—chemical metaphors, really – we crafted a strategy for changing iodabenzene from just an unhappy molecule to one that our friends in Akron or Rostov-on-Don or anywhere in the world just might make. Coming up with that strategy, that was being quintessentially human.

More "What Makes Us Human" podcasts are available on iTunes and Soundcloud.